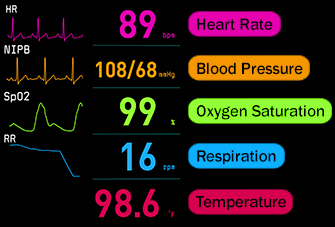

I was paged to assist a nurse with a “Rapid Response” and the nurse was concerned about her patient who was on the medical floor because of complications from c. difficile colitis. Her oxygen had to be increased from 2 to 4 liters per nasal cannula in the last hour to maintain 92% oxygen saturation.

She had a baseline respiratory rate of 24-28/minute and was now 32/minute.

She had coarse breath sounds bilaterally that was her baseline but had gotten worse.

As I assessed the patient, I too heard coarse rhonchi bilaterally, but wanted to determine if it was upper or lower in origin, so I did one thing that the newer primary nurse did not do, I auscultated both sides of the neck and could hear the rhonchi even louder.

This one assessment “pearl” quickly identified the problem of upper airway secretions as the primary problem and the need for nasopharyngeal suctioning to improve oxygenation.

I guided the primary nurse to perform this skill that she had not done before in the clinical setting and large, copious amounts of thick secretions were removed with a prompt increase in oxygenation to 96% and decrease in respiratory rate from 32 to 24.

Significance of the “Little” Things

It is the subtle findings and LITTLE things the nurse notices when performing a physical assessment that can be the BIG things that can lead to recognizing a potential problem before it needlessly progresses and results in failure to rescue.

Nurses must be able to identify EARLY changes that are subtle yet clinically significant. This requires thoroughness and attention to detail as well as clinical experience.

In this scenario, the nurse did an excellent job of clinical reasoning by recognizing the TREND and RELEVANCE of clinical data that was moving in the wrong direction, and then INTERPRETED (Tanner, 2006) the need to do something to intervene by paging a Rapid Response.

But the takeaway for this nurse was the need to include this “pearl” of physical assessment to auscultate the neck so that a problem could be recognized and nursing interventions to address this problem would then be implemented sooner that included the need to suction to improve oxygenation and prevent aspiration.

The Current Problem

The majority of nursing students who graduate are not “practice ready”. In a recently published article A Crisis in Competency only 23% of graduate nurses were able to demonstrate practice readiness by identifying and then managing a clinical scenario that required a nursing intervention.

What is a contributing factor to this current dilemma?

Nursing students are overwhelmed with the amount of content they are expected to master and as a result struggle to use and apply the most important content to practice.

The way that physical assessment is currently taught may be a contributing factor to a lack of practice readiness.

Though there are only 30 physical assessment skills that nurses consistently use in the clinical setting, students in some programs are taught well over 100 specific assessment skills (Kohtz, Brown, Williams, & O’Conner (2017), most rarely if ever used (see last weeks blog for more).

Physical Assessment Pearls

In addition to teaching the most important physical assessment nursing skills, HOW these skills are performed will influence the quality of the clinical data collected.

As a nurse in practice for over 30 years, and using my lens as a nurse educator, I would like to share some practical pearls that I have learned that can help strengthen students’ physical assessment skills.

This content is detailed in greater depth in the student text THINK Like a Nurse, chapter 10 Essentials of Clinical Practice.

Respiratory

Breath sounds

- Posterior auscultation is always preferred because there is less body tissue and adventitious breath sounds can readily be identified if present. Remember, the right lower lobe is easier to auscultate from the back.

- If coarse rhonchi are present, auscultate the neck to see if the intensity of the rhonchi increase compared to lung fields. If present, the likely source of rhonchi is upper airway secretions that may need to be suctioned.

- ALWAYS start at the top and compare one lobe laterally to the opposite side, listening carefully for not only the presence of abnormal sounds but also the quality of the aeration. If pneumonia or pleural effusion is present, the only assessment finding could be diminished aeration and this is the easiest way to determine if this finding is present.

- ALWAYS listen very carefully at the mid/lower lobes because this is where most adventitious sounds start, especially crackles, because of gravity

- If crackles are present, the degree of coarseness correlates with the amount of fluid in the alveoli. For example, fine crackles represent small amount of fluid or even atelectasis, while coarse crackles reflect more fluid in the alveoli. This is a clinical RED FLAG.

Cardiac

- Diaphoresis is ALWAYS clinically significant and reflects sympathetic nervous system stimulation. The nurse must step back and ask: WHY is this present? What is most likely causing this assessment finding based on the patient’s story and most likely/worst possible complication?

- Orthostatic BPs: Positive orthos…remember the number 20. INCREASE of HR >20 or DECREASE in systolic blood pressure (SBP) > 20 from lying to standing represent a positive orthostatic BP. From what I have observed in clinical practice, with mild to moderate volume depletion, you will typically see HR increase with no change in SBP. If both the HR INCREASES and SBP DECREASES, then the fluid volume deficit is much more pronounced in severity and is a clinical RED FLAG

Use the mnemonic “All Patients Take Meds” (APTM) to help you remember the correct sequence of a cardiac valvular assessment. The Aortic valve is second intercostal to the RIGHT of the sternum. The manubrium is the “bump” on the top end of the sternum that is the landmark for the second intercostal space.

- The Pulmonic valve is also second intercostal across the sternum on the LEFT side.

- The Tricuspid valve is fourth to fifth intercostal on the LEFT side of the sternum. This level is also consistent with the nipple line of men, and is the lower third of the sternum to visualize for women.

- The Mitral valve is the same intercostal level. Just slide the stethoscope over to the LEFT mid-clavicular. On a male, this is typically right at the left nipple. This is also the location for an apical pulse.

ACTION Steps

To take action and improve practice readiness of physical assessment in your program, take the following steps:

- Interject practical “pearls” that you have developed as a nurse in practice in your content to bring needed contextualization and relevance to teaching physical assessment regardless of the textbook used.

- Carefully review how physical assessment is currently taught in your program. Do you emphasize the 30 skills that students will do consistently? Or do you teach skills that will be rarely if ever used?

- Dialogue as a team to determine the 30+ skills you want your students to master and acquire DEEP learning of most important. (see last weeks blog for a recommended list of the top 30!) The ABCs of physical assessment are an excellent place to start!

In Closing

Strengthening nursing education so graduate nurses are well prepared for practice must be the guiding principle for everything that is done in nursing education.

In addition to thinking like a nurse using the skill of clinical reasoning, performing a physical assessment with excellence and attention to detail can make the difference between rescue and failure to rescue when a patient complication begins to develop.

Emphasize NEED to know aspects of physical assessment and use your “pearls” and the “pearls” in todays blog to get students on their way to being well prepared for real-world professional practice!

What do you think?

How have you strengthened student learning of physical assessment in your program?

Comment below and let the conversation begin!

References

- Kavanagh, J. & Szweda, C. (2017). A crisis in competency: The strategic and ethical imperative to assessing new graduate nurses’ clinical reasoning. Nursing Education Perspectives, 38(2), 57-61.

- Kohtz, C., Brown, S.C., Williams, R., & O’Conner, P.A. (2017). Physical assessment techniques in nursing education: A replicated study. Journal of Nursing Education, 56(5), p.287-291.

- Tanner, C. A. (2006). Thinking like a nurse: A research-based model of clinical judgment in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education, 45(6), 204–211.

Keith Rischer – PhD, RN, CEN

As a nurse with over 35 years of experience who remained in practice as an educator, I’ve witnessed the gap between how nursing is taught and how it is practiced, and I decided to do something about it! Read more…

The Ultimate Solution to Develop Clinical Judgment Skills

KeithRN’s Think Like a Nurse Membership

Access exclusive active learning resources for faculty and students, including KeithRN Case Studies, making it your go-to resource.