Last year Linda Caputi asked me to write an article on clinical reasoning for her annual Innovations in Nursing Education volume that she edits for the National League for Nursing.

As I reflected on what I should write that would contribute to the body of knowledge on this essential topic, I decided to emphasize WHY clinical reasoning is not on option, but foundational to nursing practice.

Volume III Building the Future of Nursing was published earlier this year with my article “Why Clinical Reasoning is Foundational to Nursing Practice”.

In order to teach students to clinically reason, it must first be defined as well as deeply understood. That is why I will highlight the most important points from the article I wrote that will define and strengthen your understanding of this nurse thinking skill so it can be effectively taught to your students!

Nursing Education…Still in Need of Radical Transformation!

It is time to rethink and question long held assumptions in nursing education.

Why?

Because the current structure of nursing education does not adequately prepare students for clinical practice. To be prepared for clinical practice and think like a nurse, students’ must understand and then incorporate clinical reasoning into their practice (Benner, Sutphen, Leonard, & Day, 2010).

Therefore, it is the responsibility of nurse educators to ensure that every student has clinical reasoning skills before they graduate (Jensen, 2013).

Though it has been six years since this groundbreaking research was first published, change comes slow and much work remains to be done to make clinical reasoning foundational to everything that is done and taught in nursing education.

Moving Beyond the Traditional Care Plan

In last week’s blog I questioned the effectiveness and relevance of the traditional written care plan to help students think more like a nurse.

Though nursing process is an important aspect of how a nurse collects and processes clinical data, it is NOT the same as being able to clinically reason.

How do You Define it?

Remember when critical thinking was the rage in nursing education? Though critical thinking remains relevant to nursing education and practice how do YOU define it?

There are literally 101 definitions in the nursing literature and many definitions are ambiguous and open to interpretation.

Because of a lack of clinical experience and lack of context, nursing students tend to be concrete, textbook learners (Benner, 1984).

Therefore critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and everything that is taught must first be concretely and succinctly defined before students can readily grasp, understand, and then apply clinical reasoning.

Clinical Reasoning Defined

A practical, working definition that captures the essence of clinical reasoning to nursing practice is found in the work of Patricia Benner:

Clinical reasoning is the ability of the nurse to think in action and reason as a situation changes over time by capturing and understanding the significance of clinical trajectories (Benner et al., 2010), the ability to focus and filter clinical data in order to recognize what is most and least important so the nurse can identify if an actual problem is present (Benner, Hooper-Kyriakidis, & Stannard, 2011).

Derived from this definition of clinical reasoning are four primary components of clinical reasoning:

- Think in action and reason as a situation changes

- Identify relevant clinical data

- Understand the significance of clinical trends of relevant data

- Make a clinical judgment to determine if an actual problem is present

1. Think in action and reason as a situation changes

Patients do not typically stay static over time, but either improve or gradually or quickly deteriorate.

Therefore, students must be prepared to think on their feet and recognize the nursing priority when the status of patients change and be skilled in early recognition and management if a change in status occurs.

A problem must be ANTICIPATED then RECOGNIZED when it occurs before the nurse can intervene and do something about the problem (del Bueno, 2005).

ANTICIPATING and even EXPECTING the most likely or worst possible complications for each patient develops the skill of being PROACTIVE and not REACTIVE in clinical practice.

Asking the RIGHT questions can help develop clinical reasoning. See past blog on what questions must be asked in the clinical setting.

2. Identify relevant clinical data

TMI (too much information) in nursing education is a barrier to student learning and mastery of content (del Bueno, 2005).

To develop a sense of salience and identify what clinical data just collected is most relevant, students must FIRST develop a DEEP understanding of the applied sciences that include pathophysiology, pharmacology and fluids and electrolytes.

This knowledge is then applied in the clinical setting when analyzing physical assessment findings, vital signs (VS), and laboratory values for each patient that is cared for.

Once clinical data are correctly identified as relevant, the next step of clinical reasoning is to trend this data to determine the clinical trajectory or TREND that the patient data is suggesting (Benner, Sutphen, Leonard, & Day, 2010).

3. Understand the significance of clinical trends of relevant data

Identifying and trending the most important or relevant clinical data by comparing current data to previous readings is an essential component of clinical reasoning and a hallmark of thinking like a nurse (Benner et al., 2010).

To “rescue” a patient with a change in status, the nurse must be able to recognize subtle changes in the patient’s condition over time.

“Rescue” is facilitated when the nurse trends relevant clinical data and is intentionally assesses early manifestations of the most likely or worst possible complication.

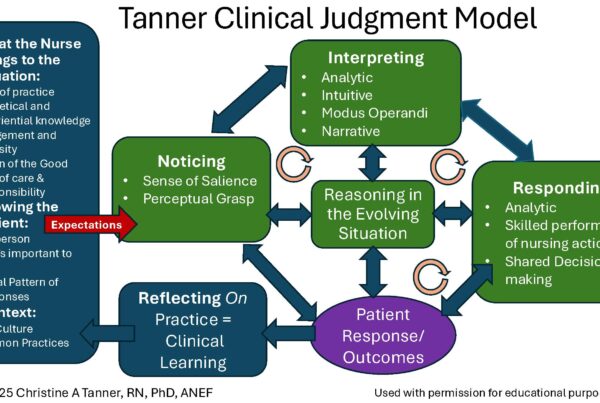

4. Make a clinical judgment to determine if an actual problem is present

Clinical judgment is the end result and hallmark of professional practice.

Clinical judgment can be defined as the interpretation or conclusion about what a patient needs and/or the decision to take action or not (Tanner, 2006).

Failure to take action can equal failure to rescue and result in an adverse outcome or even patient death.

If a nurse in practice is unable to clinically reason, the results can be an incorrect clinical judgment.

To consistently formulate safe and correct clinical judgments, the nurse must be able to USE knowledge, integrate nursing process, think critically, and use clinical reasoning to make a correct clinical judgment (Alfaro-Lefevre, 2013).

For more, see past blog How to Strengthen Student’s Ability to Make a Correct Clinical Judgment.

In Closing

Though it is imperative that clinical reasoning be correctly understood, that is not enough. Clinical reasoning like everything else in nursing education must be able to be PRACTICED so it can be applied to the bedside!

I have numerous clinical reasoning tools and case studies that will help contextualize this essential skill.

Nurse educators must ensure that every student is able to USE and APPLY clinical reasoning to ensure safe, quality care that will result in improved patient outcomes before graduation.

Failure to do so can be a matter of patient life or death!

What do you think?

How do you emphasize and integrate clinical reasoning in your class and clinical settings?

Comment below and let the conversation begin!

References

- Alfaro-LeFevre, R. (2013). Critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment: A practical approach. (5th ed.). St. Louis: Elsevier–Saunders.

- Benner, P. (1984). From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Benner, P., Sutphen, M., Leonard, V., & Day, L. (2010). Educating nurses: A call for radical transformation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Benner, P., Hooper-Kyriakidis, P., & Stannard, D. (2011). Clinical wisdom and interventions in acute and critical care: A thinking-in-action approach. (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

- del Bueno, D. (2005). A crisis in critical thinking. Nursing Education Perspectives, 26(5), 278–282.

- Jensen, R. (2013). Clinical reasoning during simulation: Comparison of student and faculty ratings. Nurse Education in Practice, 13, 23-28.

- Tanner, C. A. (2006). Thinking like a nurse: A research-based model of clinical judgment in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education, 45(6), 204–211.

Keith Rischer – PhD, RN, CEN

As a nurse with over 35 years of experience who remained in practice as an educator, I’ve witnessed the gap between how nursing is taught and how it is practiced, and I decided to do something about it! Read more…

The Ultimate Solution to Develop Clinical Judgment Skills

KeithRN’s Think Like a Nurse Membership

Access exclusive active learning resources for faculty and students, including KeithRN Case Studies, making it your go-to resource.